The interaction of genetic and environmental factors, the concept of resilience and risk, and protective factors for BESD

This unit examines the complex interaction of genetic and environmental factors that influence behaviour and looks at how our interpretation of behaviour can be influenced by our understanding of these factors. It considers how the effect of genetic and environmental risk factors can be lessened through good classroom practice.

The unit covers:

- The interaction of genetic and environmental influences on behaviour

- Resilience and risk factors for BESD

- Protective factors that can decrease the risk of children developing behavioural problems

The history of BESD factors

Use the timeline slider to see how the consensus of opinion on BESD has changed over time.

1960s

In the 1960s there was broad acceptance of the lasting and irreversible effects of early childhood experiences. There was also a consensus that social disadvantage was a major cause of BESD.1980s

During the 1980s, research found that the same or similar environmental factors could lead to a range of outcomes between various individual cases. Because of this, the onus started to move away from the child’s environment.Today

Current approaches recognise a complex relationship between environmental and genetic factors. In Genes and Behaviour: Nature-Nurture Interplay Explained (2006), Sir Michael Rutter argues that environmental factors will influence a genetic predisposition towards behavioural problems, either by increasing or decreasing its effects.

- 1960s

- 1980s

- Today

Methodologies of genetic research

Quantitative genetics

This methodology is based on quantifying how genetic and non-genetic factors, such as the surrounding environment, determine the consistent occurrence of particular traits or disorders within groups of people.

This approach mainly uses twin and adoption studies, both of which focus closely on the relative influence of the aforementioned factors on human development.

The general principle of this methodology is that variation in quantitative traits is caused by the cumulative, small effects of lots of genes, combined with environmental factors.

Studies using quantitative genetics have found major interplay between the two factors, and as such suggest that disorders cannot be exclusively attributed to either.

Environmental resilience

Bonnie Benard’s 1991 book, Fostering resiliency in kids, found that half to two-thirds of children growing up with environmental contributors to BESD were eventually able to adapt to normal behaviour. Her data sample included populations of:

- Children with mentally ill, alcoholic, abusive, or criminally involved parents.

- Children growing up in war-torn or economically depressed regions.

Resilience-enhancing classroom practice

In Promoting Resilience in the Classroom (2008), Carmel Cefai describes the main attributes of resilience-enhancing classroom practices.

- Caring classrooms

- Prosocial classrooms

- Engaging classrooms

- Empowering classrooms

- Learning-focused classrooms

Caring classrooms: classroom environments which encourage genuinely caring and emotionally engaged relationships between teachers and pupils.

Prosocial classrooms: classrooms which stimulate positive social interactions and encourage caring, supportive peer relationships.

Engaging classrooms: classrooms that focus on meaningful and inclusive engagement with the learning material.

Empowering classrooms: classroom environments that encourage pupils to make choices and participate in decisions.

Learning-focused classrooms: classrooms in which pupils share common purposes and learning-related values.

UK Resilience Programme

In September 2007, the Government launched the UK Resilience Programme (UKRP) in a pilot with Year 7 pupils across 22 schools in three local authorities. More schools have since started teaching the programme, which is aimed at improving psychological wellbeing and building emotional resilience in 11- to 13-year-old pupils.

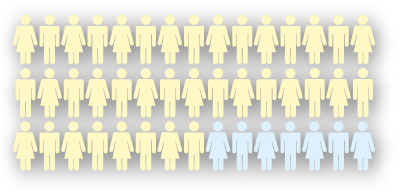

The DfE’s final evaluation report on the programme (PDF, 3.5MB), published in April 2011, took qualitative interviews with 45 pupils to show how they had used skills learned in UKRP lessons to deal with problems in real life. As represented in the diagram, more than four fifths were able to provide an example of this.

See a breakdown of pupils' responses

The interviews indicated that 38 out of 45 students were able to give an example of using UKRP skills to deal with real-life problems. These tended to focus on tangible problems such as avoiding arguments, shouting or having fights. They also included cases of being assertive, negotiating agreements or using relaxation techniques.

The pupils said they used UKRP skills in order to:

- Make themselves feel better (10 pupils)

- 'Not rise' to provocation (17 pupils)

- Employ assertiveness and negotiation techniques to address problems (5 pupils)

- Overcome procrastination (2 pupils)

- Reject negative beliefs (4 pupils)

Four pupils did not use any skills; three provided insufficient detail.